London’s Burning

Imagine if you walked unsuspectingly into your classroom one day after lunch and found an apparently random collection of objects strewn all over the floor…a wine bottle (empty, before you ask!), some cheese, a few biscuits and a little bit of spilt flour. What would you think? Had the teachers forgotten to put away their shopping? Had they been having a party? The children in 2HM were very puzzled but, looking more closely, they saw some other things…pictures, a pair of masks on sticks, a mop cap and a long curly wig.

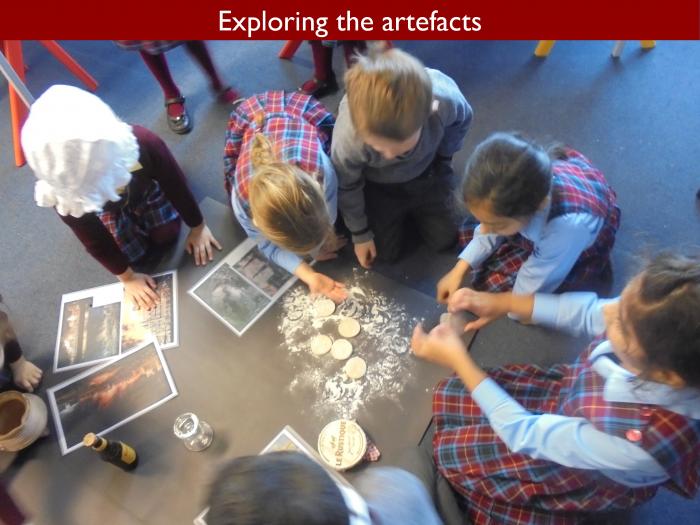

Now it seemed as though someone was trying to tell them something. A mystery from the past, perhaps? Miss Murphy invited the children to gather round the artefacts. They could explore the objects by looking and touching, she told them, and they had to come up with questions based on what they could discovered. It was all tremendously exciting. Luna loved touching the floury biscuits. Ruben was desperate to pick up one of the artefacts, but Muhammed admitted that initially he found them quite confusing. As the children asked questions, however, they began to see the links between the objects on the carpet.

We often like to begin a lesson by posing a question. Not only does a question immediately engage children and encourage them to make links with what they already know, it also helps them to take more ownership of their learning. Alexander was quick to make sense of the objects in front of him. “There’s a book in the library called Plague and Fire,” he told everyone. He realised that the link between the artefacts must therefore be the Great Fire of London.

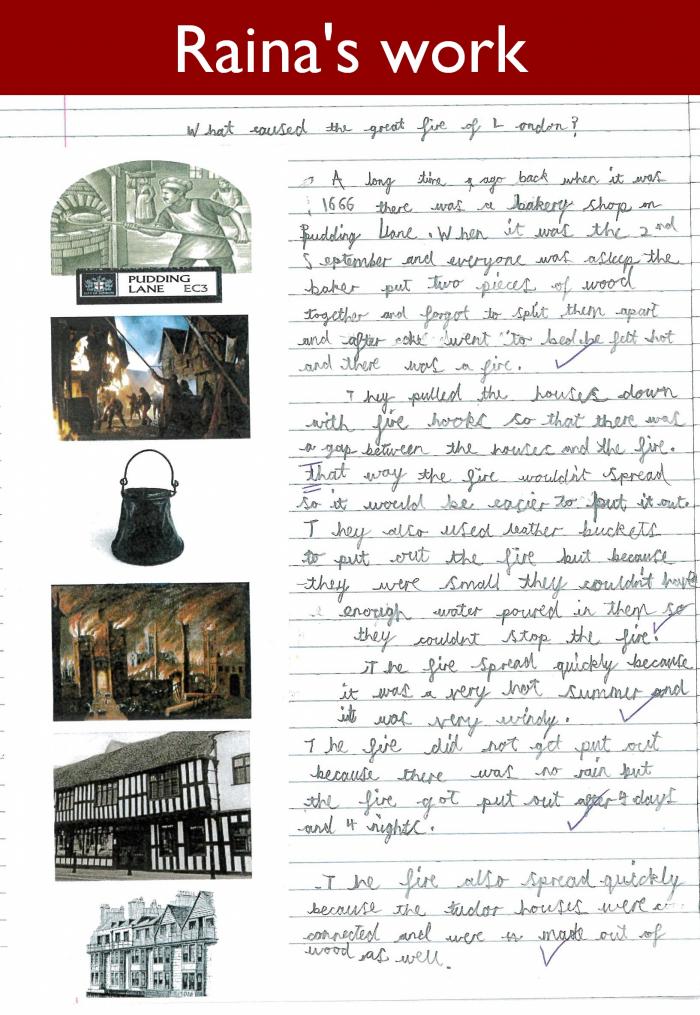

School wouldn’t be school without a lesson on the Great Fire of London, and Miss Murphy wanted the children to understand why the fire had started, why it had spread so quickly and why it had caused so much devastation through such a large part of the city. She also wanted to introduce the children to the character of Samuel Pepys, whose famous diary provides us with valuable source material about the events of September 1666. Pepys was a rich man, employed in the service of the government, and he enjoyed the finer things in life, such as expensive wine and cheese. Famously, he had his servants bury his whole parmesan in the garden before he fled his home in Seething Lane at the height of the fire.

What happened in London was by no means unusual in the Seventeeth Century. Fire was a terrible scourge in England at this time. There were significant fires in the city in 1633 and 1643, and in 1650 a fire in Tower Street caused seven barrels of gunpowder to explode, rendering 41 houses uninhabitable. There was also a major fire in Warwick in 1694, which destroyed much of the town centre and damaged St Mary’s Church.

In 2HM, the children watched a short film which illustrated clearly how the construction of medieval buildings made them vulnerable to fire. Although thatching had been banned as long ago as 1200, London was such an important city that as many houses as possible had to be crammed in to very small spaces. Wood was the chief material for building and, in order to create extra dwelling space, people made the upper storeys of their houses wider, causing them to overhang the street below. This practice, known as jettying, made it all too easy for fire to spread.

As Raina observed, another reason why the fire spread quickly was because it was the end of a long hot summer, and everything in London was tinder dry. People took desperate measures to fight the inferno. Although fire fighting was in its infancy, leather buckets were used to bring water from the River Thames. When that proved futile, Gurleen learnt that a decision was taken to pull down houses to halt the spread of the fire. It was a lottery which way the flames would travel, but eventually a change in wind direction caused the fire to blow back across previously burnt areas and die down.

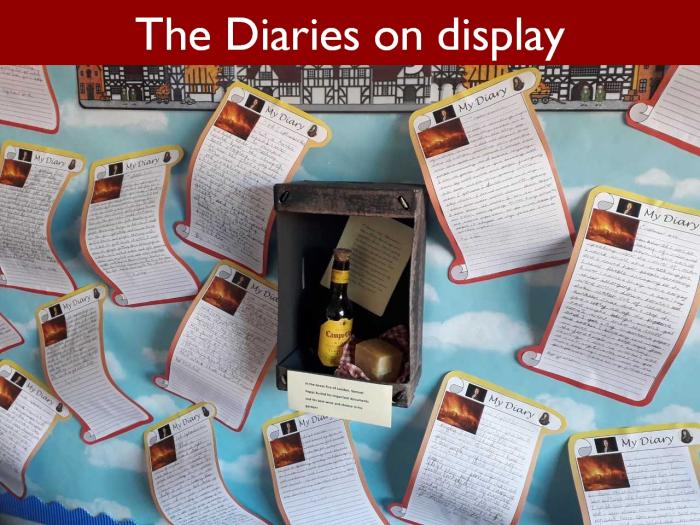

The devastation was immense. Over 13,000 houses were lost, as well as 87 churches and St Paul’s Cathedral. Yet it seems that fewer than ten people died as a direct result of the blaze, presumably because the proximity of the river provided an ideal escape route. Samuel Pepys was one of the lucky residents whose house escaped the flames. He was able to go home, dig up his parmesan and continue recording events for posterity with his elegant quill pen. In their next lesson, the children will put themselves in the shoes of Pepys and describe their experiences in their own Fire of London diary.

Once the clear up began, Londoners discovered that there had been at least one positive amidst all the horror. The fire wiped out the rat population of the city. The rats, of course, carried fleas which spread the bubonic plague that had killed so many people only the previous year. The Great Plague was the starting point for an exciting visiting workshop enjoyed by both classes in Form 2 last week. Jessica, the workshop leader, was amazed how knowledgeable the children were. As part of the workshop, the children had the chance to express through movement and drama the emotions experienced by people in London during the plague and fire. Eva felt ashamed that she had forgotten to damp down the oven in her house at Pudding Lane. Luna, meanwhile, felt very sad to be crossing the Thames in a rowing boat, watching the city burn out of control.

London is unrecognisable now from the days of the Fire of London. If you visit Pudding Lane today, you will find that the streets are lined not with medieval buildings but with shiny modern office blocks. Only the Monument, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, reminds us what happened there all those years ago. However, I am sure that, when I read 2HM’s Fire of London diaries, their super descriptive writing will immediately transport me back to those terrible days at the beginning of September 1666.