Shakespeare Week: The Show Must Go On

Shakespeare Week has become a March tradition for Form 5 at Eversfield and this year was no exception. Looking back, it’s impossible to overstate what an achievement it was for pupils and teachers alike. In common with any fine troupe of actors, they proved above all else that, whatever is happening in the world, the show must go on.

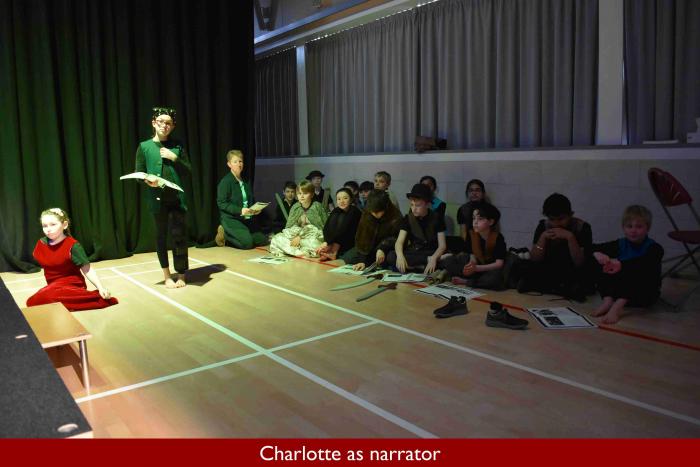

Every year, Mr Hastings and his team select a different play to rehearse and perform in the space of just a week. Lines are learnt in lieu of other homework, stage directions practised and understood, and children conquer their nerves in order to project their voices sufficiently to fill the whole of the JSB. This year, the cast also had to grapple with absences, understudying and last minute adaptation, and they did so magnificently.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the choice for 2020, is one of Shakespeare’s famous comedies and is set in woods just outside the city of Athens. The plot initially appears bewilderingly complex and consists of several linked, parallel narratives, similar in a way to today’s continuous TV dramas.

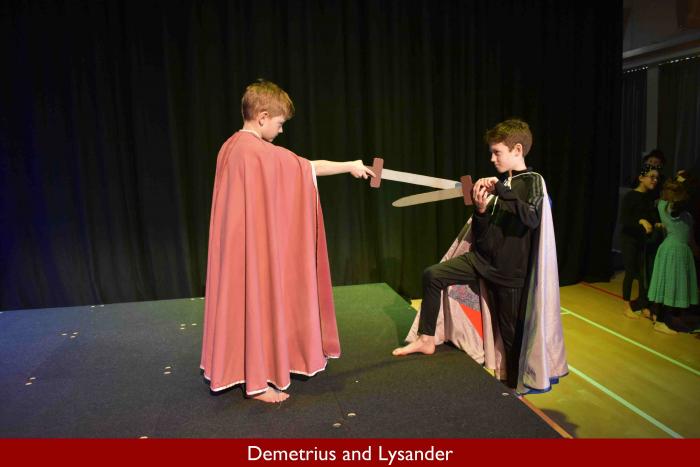

Preparations are afoot at court for the marriage of Duke Theseus, played by Nihaal, and Lily in the role of Hippolyta, the Queen of the Amazons. Meanwhile, we have the problem of Hermia (Aiyana), who doesn’t want to marry Demetrius (Daniel), even though her father Egeus (Rafael) says she must. She wants to marry a man named Lysander, played in turn by Suleiman and Noah, and hopes that Demetrius can be persuaded to marry her best friend Helena (Tayla) instead, leaving Hermia and Lysander to fulfil their dream. The action then shifts to the woods, where Hermia flees, having been told that she will be confined to a nunnery if she doesn’t marry Demetrius.

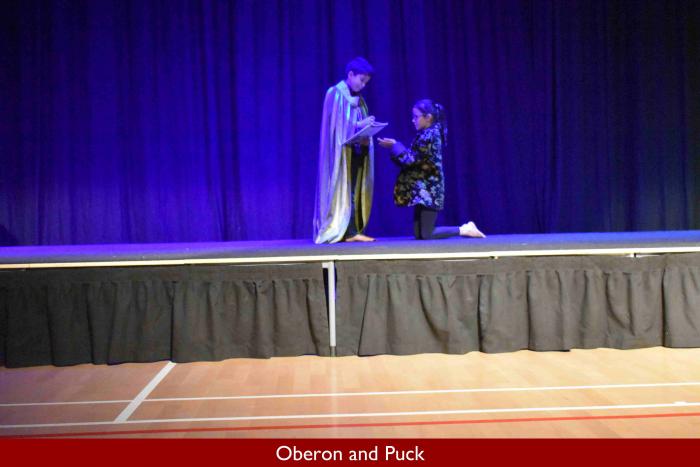

The wood is home to fairies, including King Oberon and Queen Titania and Oberon’s servant Puck. I should point out that the roles of Oberon, Titania and Puck required so much learning that they were shared between Suleiman and Karan, Alice and Maryam, and Eva, Grace and Lucy respectively. Oberon plans to play a trick on Titania by use of a magic flower, which will make her fall in love with the first thing she sees. Later, hearing of the woes of Hermia and Lysander, Oberon decides to use the magic flower on Demetrius as well to help out his human friends.

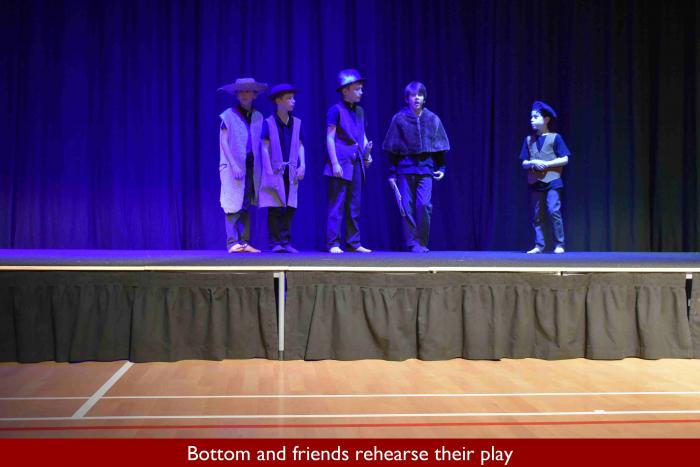

Also in the wood, in typically Shakespearean style, are a group of rustic characters who are rehearsing a play to perform at Theseus’ wedding. Chief amongst them is Bottom, a weaver, played by Tomas, whose bossiness is annoying the others. Noticing this, Puck decides it would be funny to make Titania fall in love with Bottom, giving Bottom a pair of donkey ears to make the joke even funnier. Pleased with himself, Puck is on his way back to Oberon when he comes across Hermia and Lysander sleeping in the wood. Assuming that Lysander is the one who needs the magic flower, he administers a dose, which has the disastrous effect of making Lysander fall in love with Helena. What a muddle!

Poor old Puck is in trouble with Oberon. He tries to rectify the situation by giving Demetrius some of the magic flower potion, meaning that both Demetrius and Lysander think they love Helena, and no-one loves Hermia. This makes Hermia very cross indeed. Finally, everything is happily resolved. Everyone loves who they are supposed to love, and the fairies use their magic potion to bless everyone with happiness. The play concludes with the wedding of Theseus and Hippolyta, and the whole cast take a rousing round of applause.

For the purposes of Shakespeare Week, the children were issued with a specially adapted playscript designed for use in schools. Even so, they had to adjust quickly to the unfamiliar Shakespearean language, dating back more than 400 years. Many words in Shakespeare are unfamiliar to modern ears, and phrases are often constructed differently, which of course makes it much harder to learn off by heart. Mr Hastings believes it is instructive for children to realise that language is continuously evolving. If you compare Shakespeare to the work of Chaucer from the fourteenth century, you will notice a huge difference, as indeed you will if you compare children’s fiction written one hundred years ago to that published today, where the influence of American English is much more to the fore. What impressed me was how successful the children in Form 5 were at learning their lines. Where scripts were needed, it was only because parts had to be swapped around between the cast at short notice.

It was such a pity that it wasn’t possible for us to have parents watching the performance on the last Friday before we closed. We certainly missed you, but you should know that your children did you proud. Every single one of them. Mrs Leonard-Cross, the prompter, sitting in the shadows with her handy torch to light up the script, had astonishingly little work to do. The audience, consisting of Forms 2, 3, 4 and 6 and their teachers, were spellbound, and that is testament to the way in which Form 5 rose to the challenge in understanding and conveying the story. Speaking to the children afterwards, I could tell that they were thrilled with what they had achieved and are keen to tread the boards again just as soon as they can.