Frozen in Time

We have all heard of fusion cooking, but you can have fusion lessons, too, and they are often some of the most successful and rewarding experiences for children and teachers alike. Learning has a habit of breaking out of subject specific boxes, and so it should, because that is how links are made in children’s minds. Not long ago, I blogged about the activities of 4ML in PE, a prime example of a fusion lesson. When Mrs Hastings helped 6AB examine the effect of the eruption of Vesuvius on the Roman town of Pompeii, she was in effect teaching a history lesson, drawing on a very similar skill set to the type Mr Leonard would employ.

The pupils in Form 6 have been exploring mountains in Geography this term. Recently, they have discovered that mountain ranges can be formed as a result of folds or faults in the earth’s crust. In addition, mountains can also be formed as a consequence of volcanic action. Think of Arthur’s Seat in Edinburgh or the ring of mountains surrounding Clermont Ferrand in France.

The children are well aware that volcanoes can be classified as active, dormant or extinct. Of the numerous active volcanoes in the world, Vesuvius is perhaps the most iconic, a looming backdrop to the glorious Bay of Naples; beautiful but deadly. 6AB impressed Mrs Hastings with the technical knowledge about Vesuvius that they brought to the lesson. It was a dust volcano, they explained, and Seth was able to tell the class about its pyroclastic flow, by which he means fast moving waves of hot toxic gas and ash, flowing out of the volcano at ground level.

The last major eruption of Vesuvius occurred in 1944, amid the chaos and carnage of World War II, but the event that most people know about took place in Roman times, in AD79, when the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were obliterated by a thick layer of volcanic ash.

The devastation occurred almost instantaneously because residents didn’t have chance to get away. The ash captured them in the midst of what had started out as a normal day. They were frozen in time, until modern archaeologists uncovered their remains and, with them, a vast wealth of detail about domestic life in the first century AD. Mrs Hastings showed the class a BBC Bitesize clip which explained how archaeologists made casts of the remains found at Pompeii by pouring plaster of Paris into moulds, capturing the victims of the volcano in eerily lifelike poses.

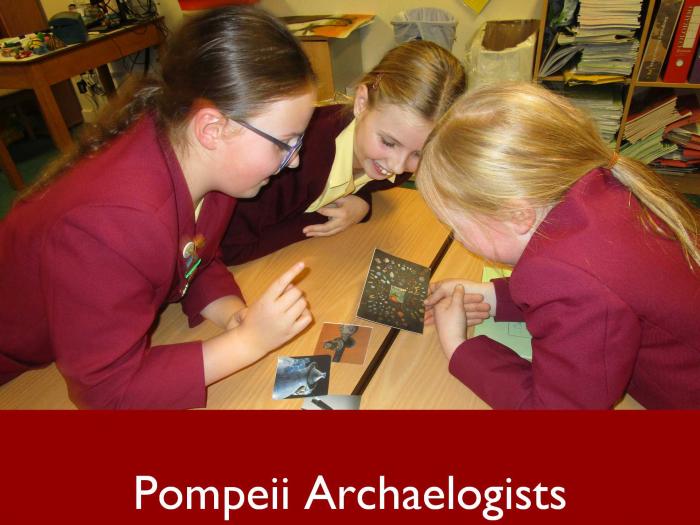

The children then played a game called Pompeii Archaeologists. Each table group was given a set of pictures showing objects found at the site, and they had to work collaboratively to identify them. A fearsome collection of medical instruments suggested the presence of a doctor’s house or an apothecary, but no-one was expecting to see a perfectly fossilised loaf of bread. Of course, the children couldn’t access the artefacts themselves and, as Seth rightly pointed out, working with images presented its own set of difficulties. There was no sense of scale, meaning that it was hard to determine if an object was a ring or a bracelet.

In the last part of the lesson, the children were given the opportunity to research further the impact of the AD79 eruption on the city of Pompeii. Ideas were shared about how the eruption indirectly informed our understanding of people’s lives so long ago. The question on everyone’s lips is always when will Vesuvius erupt again? A fundamental difference between Roman times and the present day is that the volcano is now intensely monitored. Back in AD79, people were taken by surprise and did not understand what was happening. As Malakai pointed out, they thought it meant that the gods were angry with them. Many people didn’t even realise that Vesuvius was a volcano. Even now, however, the city of Naples may get very little warning that an eruption is imminent. Personally, I find it very hard to come to terms with the fact that such an ancient and beautiful place is essentially living on borrowed time.