The Squashability Factor

Who would want to be a teddy bear in Form 2? You come to school all happy and eager, expecting to receive lots of cuddles from the friendly Eversfield children, and what happens? Mr Solly tells you that you have to take part in an investigation to find out how squashy you are and there’s no time to get away!

The topic in Form 2 this half term is Materials, which is perfect for helping young scientists to develop their skills. In this particular lesson, to explore which of the selected materials was the squashiest, the focus was on prediction skills and developing an understanding of how to structure a fair test.

To start with, to ensure that everyone was clear on what the task would involve, Mr Solly asked the children to discuss with a partner what exactly we mean when we describe a material as being squashy. For instance is the word squash related in any way to the squash that we drink or the interestingly shaped vegetables you often see at this time of year? It was immediately clear that there are several synonyms for squash, including press, crush and squish, as well as some words with similar meanings, including knead.

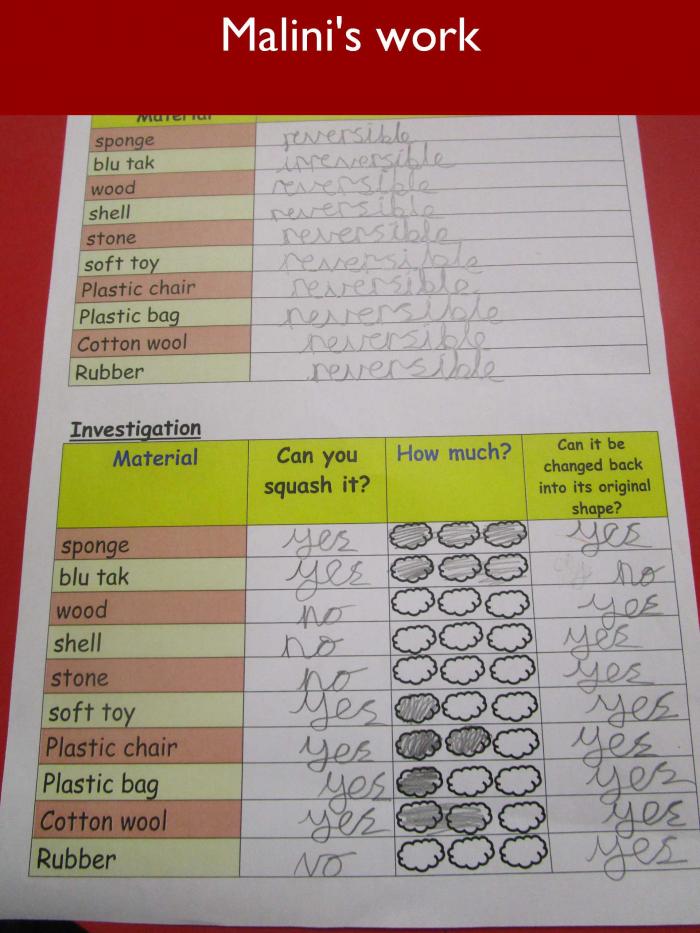

Prediction is a skill that some children find challenging, primarily because it requires them to take a mental leap of faith and run the risk of being wrong. Teachers in Lower School spend a great deal of time reassuring children that it doesn’t matter whether a prediction subsequently turns out to be incorrect. In fact, it often proves to be more interesting when the unexpected happens. What is important, however, is that children are encouraged to put forward a reason in support of their prediction, linking their ideas to previous observations or learning. In this case, the children were asked to think about whether a material would return to its original shape and size when the squashing stopped; in other words, was the change they caused to the material reversible or irreversible?

Fair testing is another tricky concept for younger children to understand, and it was particularly difficult in this investigation as Mr Solly had gathered a range of materials for testing that were all different sizes. How would the children be able to differentiate between the degree of squashability of a large cuddly toy in comparison with a small piece of blu tak or a rubber? Before the investigation started, it was vital that everyone agreed upon a means of measurement and a way of recording, and it was decided to measure the difference between the normal height of the object and the squashed height. It would therefore be fair, whatever the size of the object. In addition, Lincoln was very keen to point out that, when testing, he applied the same amount of force to each object.

The children went about their investigation with great enthusiasm, as the pictures testify. The recording sheet was structured in such a way as to make it easy for them to demonstrate how squashy each material turned out to be. In addition, the children were asked to review their predictions on reversibility, which led to a few surprises. Daniel was interested to discover that a rubber was the least squashy of all the materials he investigated, even though rubber is bendy. Could this be something to do with what is inside the material, he wondered, the part of it we cannot see?

As the lesson drew to a close, Mr Solly asked the class to consider to what extent squashy materials have a practical application in everyday life. We all appreciate a comfortable squashy cushion to lean on at the end of a long day, and what about the sole of a shoe or the pile of a carpet? Conversely, we also need hard, unsquashable materials in our lives to provide objects with stability and structure. The children were asked to suggest other materials they would like to test, and by far the most popular was galactic goo. Personally, I think I’d like to stick to squashing a teddy bear!